Mibel Aguilar, Professor of Biochemistry and Group Leader at Monash University, was born in Melbourne, Australia, to a British mother and Spanish father who had arrived in Melbourne four months before she was born. From her earliest days in school, she enjoyed studying science and also had a passion for languages, which she maintains to this day.

After high school, Aguilar enrolled in a bachelor of science program at the University of Melbourne. “I always had a fascination with understanding systems at the molecular level so I structured my third-year subjects to complete a double major in chemistry and biochemistry, selecting all the biologically relevant subjects in chemistry to fulfill the major and also the key subjects in biochemistry,” she explains. She then began a PhD program in chemistry, studying the metabolism and toxicity of paracetamol. “I knew that I wanted to be the one directing my future and in control of my work days and not be someone else’s subordinate. These two ambitions left no doubt as to enrolling in a PhD program and who I would study with,” she says. “When it came to embarking on my research training, I was lucky enough to work with a group headed by Ian Calder in Chemistry who was collaborating with Kathryn Ham in the Pathology Department on the metabolism of paracetamol.”

Aguilar joined the group soon after the time when the renal toxicity of Bex, a widely used compound analgesic, had been identified and characterized. “’Safe and gentle to the stomach’ paracetamol had come onto the market after phenacetin, the active ingredient of Bex, was found to cause serious renal problems. However, paracetamol can also, in reasonably low levels, cause severe liver failure. So the group was studying the molecular basis of this toxicity, and my project was to study the mechanism of less toxic analogues of paracetamol,” she explains. “The work was truly interdisciplinary. I synthesized a range of metabolites of the drugs, administered them to animals, collected their urine, had the histology analyzed, and also developed novel HPLC techniques to measure the metabolic profile of the drugs. That interdisciplinary approach really equipped me with the language of drug design and analysis and organic chemistry — a space that I am in the middle of to this day.”

After her PhD, Aguilar completed a postdoctoral position at St. Vincent’s Institute for Medical Research, working on developing new methods for protein analysis and purification. “This was the beginning of a very productive time building on my bioanalytical skills in HPLC drug analysis, but applying them to the much more complex world of peptide and proteins. I elected not to go overseas as this position was really the type of position I was interested in — again at the interface between chemistry and biochemistry, this time in the analytical sphere,” she says. “During this time I traveled regularly to international meetings and met all the major players in the field, and so while I was conscious of the fact that I had not taken a position in an overseas lab, I was still able to build up the network of senior contemporaries in the field.”

There are many factors that impede the increase in numbers of women in science — the combination of child bearing responsibilities and the brutal nature of publish or perish — and there is no real allowance made for any break in productivity.

- Aguilar

In 1986, the research group relocated to Monash University, where their bioanalytical work expanded significantly. “I was awarded a Monash University postdoctoral fellowship and utilized this to develop my ongoing interest in using analytical and biophysical techniques to study biomembranes. This work was initiated by PhD students Henriette Mozsolits and John Lee, and John is currently driving this area in my group today,” she says. “The membrane projects have also given me the opportunity to collaborate with a fantastic group of scientists, including David Small, University of Tasmania, on amyloids; Wally Thomas, University of Queensland, on GPCRs; and Frances Separovic, University of Melbourne, on antimicrobial peptides. More recently, my dream of collaborating with peptide scientists in Spain was realized when Enrique Perez-Paya, whom I had known since 1989, contacted me about measuring the membrane-binding of some Bcl-peptides, which has now led us into the world of apoptosis. I have also been very privileged to collaborate with Marcus Swann, one of the developers of dual polarization interferometry, and which has allowed us to study membrane structure changes and transformed our membrane research.”

Irene Yarovsky, RMIT University, was a PhD student in Aguilar’s lab from 1991 to 1994, and the two have recently re-started their collaborative research. “Mibel was my first colleague and supervisor in Australia. What luck was it!” she shares. “She is my dream colleague: enthusiastic, knowledgeable, hardworking, patient, respectful, and fair.”

Separovic agrees: “Mibel is generous with her time and encouragement, keen to help, and possessing a keen intellect; always positive and able to wrap her head around seemingly contradictory data to find a clearer path to understanding.”

In 2009, Aguilar was the first woman to be promoted to Professor of Biochemistry at Monash University. “This was the culmination of 15 years work, and it did leave me a little aimless for a few months. However, later that year I also took on the role of Associate Dean of Research Degrees in the Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, in which I had overall responsibility for the management of about 1,100 PhD and masters students,” she shares. “This was a challenging aspect to my everyday life, particularly in balancing the time to also write papers and grants and supervise students, but it was very rewarding to be in this senior leadership role where I participated in significant university policy development and implementation and saw the impact in the transformation of the next generation of research leaders and thinkers.”

Looking back, the biggest challenge of her career has been balancing research progress with family. “Family life has its own momentum and interweaving the scheduling of 8:00 am lectures with child-care drop-offs was certainly interesting in those early days!” she says. “However, the access and cost of childcare really has not become any easier today — in spite of all the rhetoric around work-life balance and gender equity.”

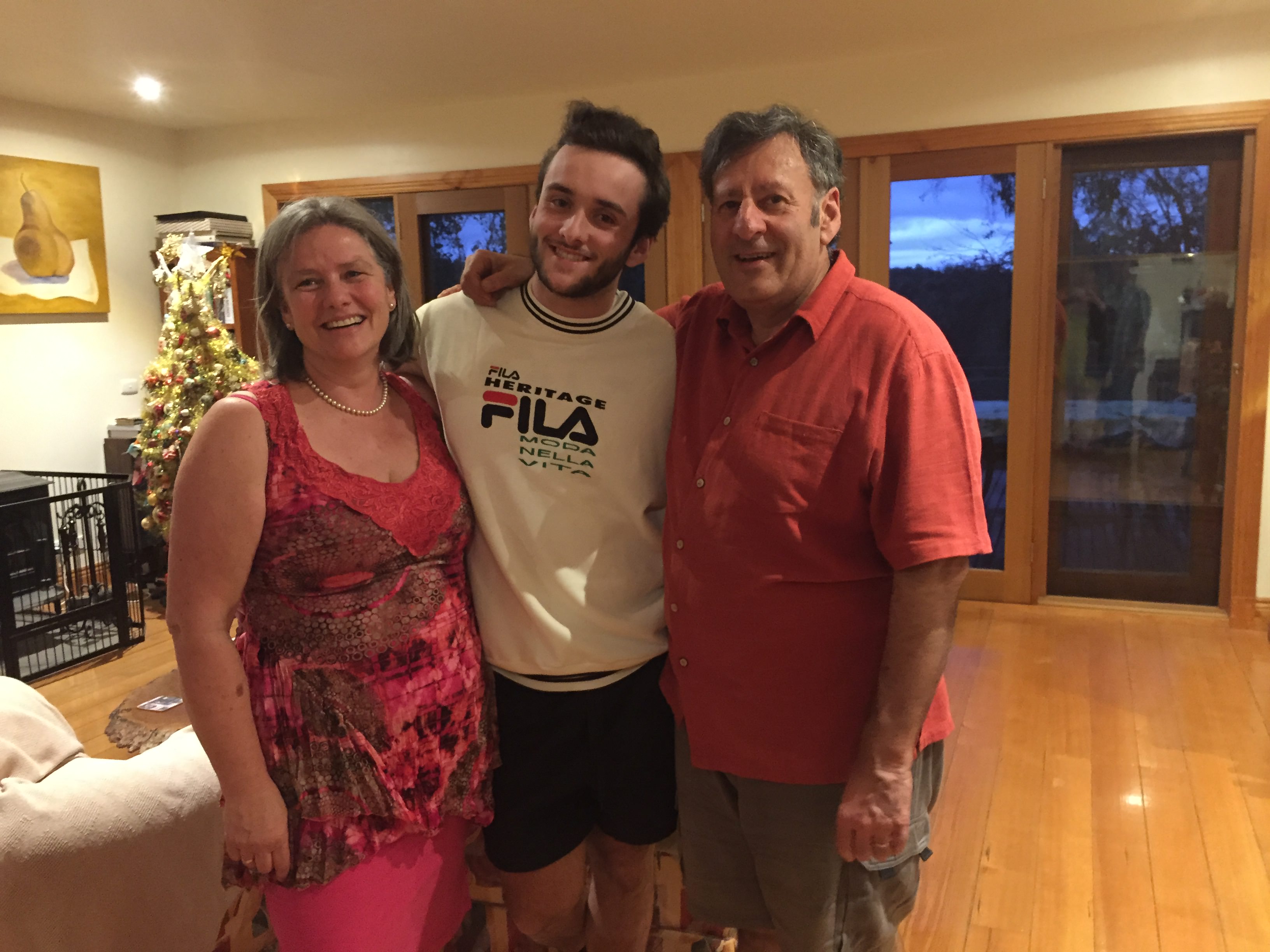

“There are many factors that impede the increase in numbers of women in science — the combination of child bearing responsibilities and the brutal nature of publish or perish — and there is no real allowance made for any break in productivity. The international conversation about this issue is now moved to plans for action, so one can be somewhat optimistic about the social landscape that surrounds us girls in science,” Aguilar says. On an individual level, work-family balance “is made a lot easier when you have supportive family and work colleagues. I was lucky to obtain a place in one of the university crèches when my son Liam was born, and so was able to go over to breast feed, which did alleviate the separation anxiety and guilt! My husband William has been legendary in his co-parenting of our son: for example, I did school drop-off and he was able to start work extremely early to do school pick-up.

The key is to be focused on specific outcomes and be strategic with commitments outside your immediate work environment so you have time for your family and yourself, “she continues.” Try also to keep a balanced perspective by reading your favorite books and maintaining some degree of physical fitness — or whatever works. You will find your own way to manage all these competing demands.”