By: Jonathan King, Eric Sundberg, and Sean Winkler on behalf of the Biophysical Society's Public Affairs Committee

The clearest and deepest expressions of our national priorities are the annual budgets voted on by our Senators and Representatives. However, the budget process is generally much less well understood than the passing of legislation. No agency of the federal government communicates back to the citizenry how their income taxes are being spent.

In the spring, when the budget allocations are being debated in the House and Senate, news outlets rarely report the actual sums being debated for the various national programs such as housing, education, environmental protection, biomedical research, infrastructure investment, Pentagon budgets, or the costs of wars abroad. Of course, the Biophysical Society and our sister professional societies report the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) budgets, but we have not routinely reported on the other categories which represent 95% of the Congressional Discretionary Budget. The Public Affairs Committee has recommended that we begin to include this information in reports to our members.

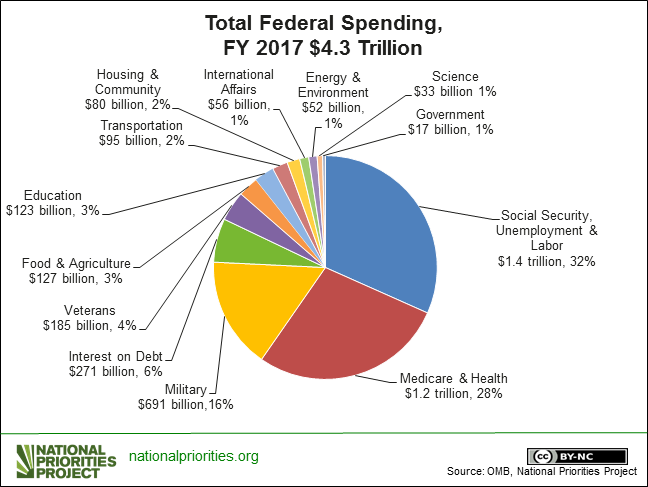

Before describing the congressional budget processes, it is important to distinguish between the annual overall Federal Budget – which includes mandatory spending and debt interest payments – and Discretionary spending – which Congress appropriates each year. In the overall budget, the majority of spending goes to the major mandatory programs, most notably Social Security and Medicare, that are trust funds; citizens pay into them in the expectation of receiving subsequent services. They are not paid by income taxes, and the funds cannot be used for other federal expenses, such as housing or biomedical research. Altering these trust funds requires explicit legislation and cannot be done through the annual budget appropriations process.

Figure 1 shows the overall federal budget for 2017.

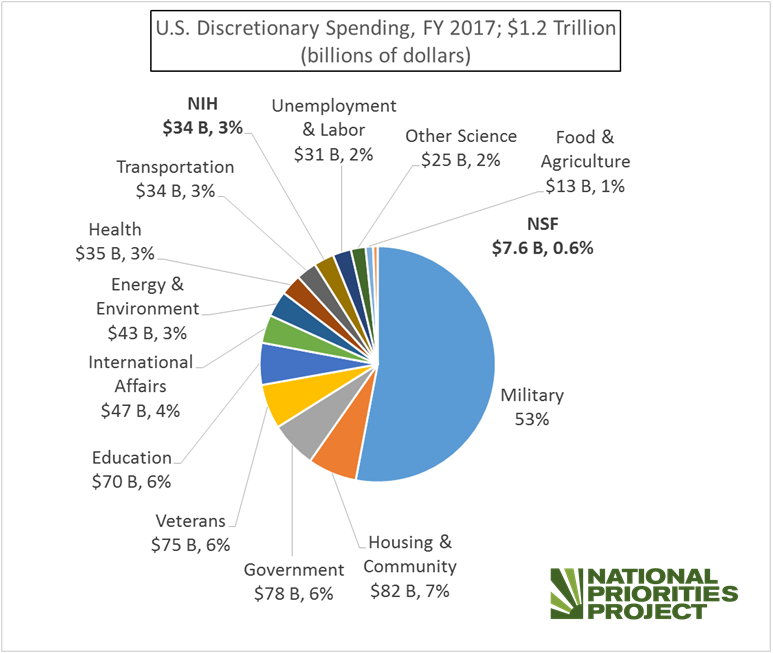

The budget category most relevant to the scientific community is the Congressional Discretionary Budget, which excludes the mandatory programs and debt payments but has all other expenditures under Congressional control. Annual appropriations bills are voted on each year by the House and Senate, with differences resolved through a joint conference. The majority of these funds are derived from individual and corporate income taxes. The funding levels, for example, for NIH, NSF, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and other agencies are specified in these bills.

The failure of Congress to pass all of its Fiscal Year 2019 appropriations bills, due to the standoff with President Trump over his request for Border Wall construction funds, led to the partial Government shutdown of the past months.

Figure 2 shows the Congressional Discretionary Budget for 2017.

The Annual Budget Process

Article 1, Section 7 of the U.S. Constitution gives to the House the power to raise revenue. Article 1, Section 9 requires that appropriations from the Treasury be explicitly decided by the Congress. Over the years various laws have been passed specifying the budget process in more detail. Currently the budget year, or fiscal year (FY), begins on October 1 and ends on Sept. 30th. The budget allocation process begins with the President introducing his budget proposals. However these proposals have no legal standing; they may influence the Congressional debate, or not. President Trump's first budget called for major cuts of 15% in NIH, NSF, Dept. of State and other civilian programs, with the intent of transferring those funds to the Pentagon budget.

The majority party in the House and Senate then brings forth their budget proposals – known as a budget resolution – for consideration. According to the 1974 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act the Congress needs to present a Concurrent Budget by April 15, for the President to sign (or veto). However, before this process can begin, the Congress must have authorizing legislation in place. Authorizing legislation confirms the existence and roles of the agencies of the government and sets out the general range of sums that can be allocated in the coming year. These bills often cover years at a time, and do not need to pass annually.

The Congressional Budget Resolution is a critically important document as it sets the total level of discretionary funding for the next fiscal year. This is known as the 302(A) allocation. This legislation is prepared by the Budget Committees of the House and Senate. For example, the division of the budget between military and civilian is essentially set in the budget resolution process. In fact, the budget resolutions even divide up the expected income among twelve Appropriations subcommittees.

The final distribution of funds is set by the twelve Appropriations subcommittees. However, some key decisions have already been made in allocating the funds available among the twelve committees in the prior Budget Resolution process. The final Appropriations bills are supposed to be complete by June 30, however, if this process has not been completed by Oct 1, the end of the prior budget year, the Congress can pass a Continuing Resolution (CR) which continues the level of spending of the prior budget year.

The government shutdown which was in place when this article was written, reflects the inability of the Congress and the President to agree even on a CR.

Though not done in secret, the allocation process essentially proceeds outside of public view. Thus at the point when the House Appropriations Committee on Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, is debating how much of the Labor and Health and Human Services funding should go to NIH, a cap has already been set on overall Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education funding by the Budget Resolution. That committee cannot take funds from the $717 billion appropriated by the Defense Appropriations Committee.

In the fall of 2018, the Labor and HHS Committee increased the NIH budget by $2 billion to $37 billion. The Biophysical Society participated in pressing for this and the outcome was considered a victory for NIH advocates. However, this still leaves the overall NIH budget at ~3% of the overall federal budget. In the same Appropriation Bill, the Defense Appropriations Committee was able to increase the various Pentagon accounts to $717 billion dollars, some 60% of the overall Congressional Discretionary Budget.

Unfortunately, the NIH may face an even harder funding environment in Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021. In Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019, Congress was able to pass a budget deal that raised the non-defense discretionary spending caps imposed by the Budget Control Act of 2011. However, no deal has yet been reached to similarly raise these spending caps for Fiscal years 2020 and 2021. Without raising the caps, the entire discretionary spending pie may be reduced by over $50 billion and many federal agencies would see significant cuts.

Our Public Affairs Committee believes that we should be calling for a budget that actually responds to the national need. We believe this is not currently the case for the NIH budget. Consider the more than 5 million Americans suffering from debilitating Alzheimer’s disease. Their care costs some 20% of the Medicare and Medicaid budgets, over $250 billion dollar/year. Yet the overall NIH investment in searching for deeper understanding, better diagnosis, and better therapies, is of the order of $1 billion/year. This is clearly an inadequate national investment given the human suffering and social and economic costs of Alzheimer’s.

What Controls the Overall Budget Allocation(s)?

The division of the budget follows the influence of major economic and social constituencies in US Society. Thus the National Association of Homebuilders presses for more housing spending; the Pharmaceutical Manufacturer’s Association generally supports NIH budgets, but opposes increases in regulations and cost controls on medical care; the National Education Association and American Federation of Teachers support increased spending on pre-K education and Title I education programs; the Defense Industry - the most powerful and best funded of all the lobbying groups - presses for increases in weapons purchases and maintenance; the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars press for increases in the Veteran’s Administration budgets. Snapshots of these efforts come from the publicly reported lobbying reports of the various groups.

The Biophysical Society works together in coalitions with a number of biomedical research groups, professional medical societies, and patient advocacy groups. Among the most important of these are the Ad Hoc Coalition for Medical Research, the Coalition for Health Funding, the Coalition for National Science Funding, and the Energy Sciences Coalition.

In the coming months the Public Affairs Committee will report to you on our relations with other allied groups in more detail, and our plans to increase the scope and effectiveness of our basic and biomedical research advocacy efforts. In the meantime, we encourage you to work with our team to take advantage of our advocacy activities. We are ready to assist you in hosting your Member of Congress for a lab tour or arranging a meeting at their District office or developing an opinion piece on your science to share with a local newspaper. We are bringing our work to you as we are piloting state and local advocacy activities in Maryland, Massachusetts, and Wisconsin this year. We will continue to provide Action Alerts to you when there are pressing science funding issues coming up for debate in Congress. To get involved in BPS advocacy, please visit - https://www.biophysics.org/Policy-Advocacy/Take-Action or contact Sean at [email protected].

For those of you who will be at the Baltimore Annual Meeting, the Public Affairs Committee is sponsoring a session entitled Understanding the Congressional Budget Process: How Science is Funded

Monday, March 4, 1:00 PM–2:30 PM

Speakers:

Tiffany Kaszuba, Deputy Director, Coalition for Health Funding

Jonathank King, Public Affairs Committee

Eric Sundberg, Public Affairs Committee

Debbie Weinstein, Executive Director, Coalition on Human Needs

Sean Winkler, Director, Public Affairs & Advocacy, BPS

Figures

These charts were prepared by the National Priorities Project, part of the Institute for Policy Studies (Washington, DC). Most of the data is derived from federal budget data published by the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB)(http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/). Additional input was from the Congressional Budget Office and occasionally other Government agencies. The categories group together the official Government categories or “functions” (which are numerical) according to common public useage, rather than strictly according to which Appropriations Committee approved them. Thus construction of Veteran’s Administration facilities are grouped with other VA budget items, even though they might be separated in the Budget Appropriation process.

Articles Sources